On any given day, a variety of planes fly over Gold Canyon. This is despite the fact that we’re not near any airports or under any commercial flight paths. If the skies can be likened to a system of roads, then I would say that the airspace over Gold Canyon is mostly a cul-de-sac; the 5000+ ft. Superstition Mountains place certain absolute limits on what sort of flying can take place in the area. Nonetheless, various planes do criss-cross our skies. On most days, ten minutes will not elapse before the sound of another airplane is heard. And this brings me to something they all have in common: they all make noise. This is how people on the ground distinguish airplanes in the sky—from the noise they make. Doubtless if airplanes made no noise, most of us wouldn’t even know they were there. The sounds we hear tend to graduate into two categories: loud enough to make us conscious of them, and loud enough to make us stop what we’re doing and look up.

Unfortunately, looking up is not likely to result in much more than what is already known: that somewhere up there is a noisy plane. The sound alone is likely to tell us more about the aircraft than anything else. For example, most of us can distinguish the sound of a jet from that of a propeller-driven aircraft. But distinguishing one tiny grayish fuselage from another at 4000+ feet? I would say that takes some skill. This brings me to another significant characteristic that most planes have in common: their anonymity. Despite the fact that all planes have a tail number—a sort of license plate for aircraft—most of us would be hard-pressed to read that number from thousands of feet below.

So when a particularly noisy plane goes by, most of us feel utterly helpless to do anything about it. We can describe the noise. We can record the time, the date, and possibly what direction the plane is flying in. But we can’t positively identify the plane. Imagine calling some municipal authority and complaining that a noisy plane flew by. Imagine the type of response you’re likely to receive. Doubtless it would be similar to the type of response you would get if you call the police and complain about a noisy automobile. Naturally, the first thing they’ll want is for you to identify it. Did you get the make, the model, the license plate? Do you at least know what color it is? No? What, the police may ask, do you expect us to do?

Most of us are conditioned to accept that noisy planes are just one of those things we have no control over, like death or taxes or the weather. We condition ourselves to accept the noise because, after all, we all benefit from airplanes. We benefit when we’re flying in them, when they’re taking us from where we are to where we want to be, when they’re bringing us packages that we order online, or when they’re simply keeping us safe. So the barriers that exist to our filing some sort of official complaint are considerable, and the greatest barrier of all is psychological.

Filing a complaint is serious business. It is not an anonymous act. It invariably puts you in opposition to someone or some entity with much greater wealth—wealthy enough to own and operate an airplane (99% of us, incidentally, do not). We also factor in the likelihood that our complaint will result in real and substantive change. Is it worth our time to complain about the noise? Will it make a difference? Most of us weigh the pros and cons and come to the same conclusion: it’s a hopeless waste of time.

So what, if anything, would allow someone to overcome such barriers? Well, what if the overwhelming majority of noise came from specific planes that fly the same routes everyday? Even better, what if you could identify the planes? What if you had an answer for every detailed question that was asked of you?—questions designed to make you doubt yourself and your own experiences and observations, designed ultimately to make you go away and accept your status as a victim of those with the means to fly over you at will.

According to Wikipedia, CAE is “the largest flight school in the world” and instructs student pilots from “Belgium, The Netherlands, the UK, Italy, Turkey and Vietnam”. All day every day, CAE creates noise and pollution in Gold Canyon. How loud is the noise from a Piper PA-28? Loud enough that the pilots themselves must wear hearing protection, as cabin noise can exceed 100 dBA. Loud enough that you can hear a Piper inside a stucco wood frame home from over two miles away. For CAE, noise is an unfortunate by-product of their business. They cast it off into the environment and never look back. But noise is ultimately like any other form of pollution. Indeed, that’s why we have the term “noise pollution”. And what do we do with companies who knowingly pollute the environment? We hold them accountable. We make them deal with their industrial waste in a responsible manner. In this case, CAE does not bear any costs for the waste they create, and it’s the residents of Gold Canyon who suffer as a result.

Moreover, the industrial waste that is being dumped on Gold Canyon is not merely excessive noise, but toxic lead. The fuel CAE’s planes use—known as avgas in the aviation industry—decomposes after combustion into microscopic lead particles that rain down upon our community. The lead is aerosolized so that it spreads out as it precipitates, meaning the planes do not have to be flying directly over you for the lead to reach you. There are no safe levels of lead; any amount is toxic—particularly to children. Commercial jet airliners, incidentally, do not use leaded fuel. But small noisy planes like these do, and they’re the largest source of lead emissions in the United States.

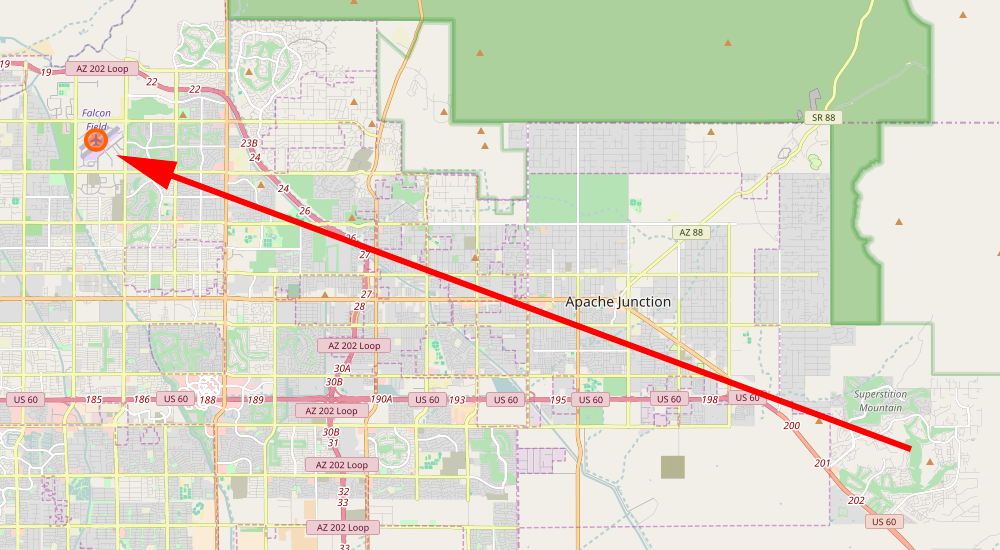

Falcon Field, the airport where CAE’s planes are based, is about four miles from millions of acres of the Tonto National Forest. One would imagine that enormous swathes of unpopulated areas would be an ideal location to fly noisy toxic-lead-spewing planes. Better for the pilots, too, as it’s a lot more scenic. But there’s a reason why CAE has chosen a corridor that routinely takes their noisy planes over Gold Canyon instead. These are student pilots, which is to say inexperienced, and CAE wants a nice simple route with no consequences. The pilots fly over a highway—S60—heading out, and parallel the same highway coming back. S60 is a large straight visual landmark easily seen from the altitude these planes fly at. The route ensures that these pilots won’t become disoriented and lost. It also ensures that if there are mechanical issues, these pilots have plenty of options. They can land on the desert near the road. Heck they can land right on the highway if they have to. You see it’s all about pilot safety; all other considerations are secondary. If disturbing 10,000 residents all day, every day, makes the pilots even 0.01% safer then so be it.

But let’s imagine for a moment that CAE was actually forced to balance the conflicting concerns of pilot safety on the one hand with the quality of life of 10,000 Gold Canyon residents on the other. Can you think of another way to ensure that student pilots won’t become disoriented and lost? Do you know what I use to avoid getting disoriented and lost? A GPS. But a GPS can fail, right? OK, so let’s get them two GPS units—one for backup. The chances of two GPS units both failing at the same time rapidly approach a very low order of probability. Obviously these student pilots are not “instrument rated”, and no one is suggesting that they use a GPS to navigate. But if the issue is one of safety and preventing student pilots from becoming disoriented, then a GPS can certainly be used in an emergency. Visual flight rules do not preclude a pilot from taking a gander at the ole GPS unit. Perhaps there’s some compelling reason why CAE doesn’t want its student pilots to have GPS units. Maybe they don’t want these student pilots to pick up bad habits and rely on the units. Perhaps. But even if that were the case, there are other options that do not involve impacting 10,000 Gold Canyon residents. Rental cars, for example, have GPS units that are content managed. They can be programmed to not show anything until you press a button, at which point the action is recorded. Instructors could easily determine who used the emergency GPS, how it was used, how long it was used, and any other metric they’re interested in. The point is that other options exist. Of course they do cost money…

As much as I would like to believe that it’s all about the pilots, I am reminded that CAE is not a charity. They are in fact, “the largest flight school in the world”—a publicly traded for-profit corporation that earns “$1.6 billion in revenue annually”. CAE’s #1 priority is not to their pilots, but to their shareholders. Of course any exec at CAE would say that there’s no conflict here; pilot safety leads to increasing enrollment and hegemony which leads to increasing profits and shareholder value. It’s all one and the same. But that’s not really true. There are always additional measures that could be taken to make these student pilots even safer, but at some point it would come at the expense of shareholder value. There are always limits where the marginal utility of additional expenditure just doesn’t pay off. You know: the law of diminishing returns. Not to digress, but did you know that you can retrofit planes to include whole plane parachutes?

Imagine that! A parachute for the entire plane—pilot and all. Of course these systems cost a bit of coin—not only to install and inspect but increased fuel costs due to the extra weight. However, there’s no doubt that a plane equipped with such a system is safer than one without. Whether or not this additional measure of safety is worth the cost is the point of this paragraph. CAE doesn’t equip all its planes with whole plane parachutes because they’ve performed a cost-to-benefit analysis and have concluded that it’s not worth it. As for impacting 10,000 Gold Canyon residents, all day, every day, well that works just peachy because it doesn’t cost CAE anything. So to claim that it’s all about pilot safety is extremely disingenuous. It’s not all about pilot safety—except when it costs CAE nothing. Then it’s all about pilot safety.

Now it’s entirely possible that CAE was somehow unaware of the costs to Gold Canyon in having their student pilots fly this particular route. And this is why we contacted them, to let them know that—yes—when your obnoxiously loud toxic-lead-spewing planes fly over us all day, every day, it does indeed have an impact on us. So we’re well past that hurdle of ignorance. I’m sure that corporations who dump their toxic waste into nearby streams and rivers are just as shocked when someone comes forward to enlighten them as to the impact such dumping has on the environment. So let’s just say that the veil of ignorance has been well and truly lifted, no harm no foul. But now it’s time for CAE to realize that this issue is not going to go away. The polluters have been identified, and they need to stop. CAE needs to balance their business interests with those of the communities in which they operate.